The Reader May Choose Either of Two Ways to Read This Blog. 1) Wade through my horrible writing style, or 2) Read the words on this photo. As regards Psalms, the photo sums up my heart.

For those who choose to wade through my arduous writing, begin here.

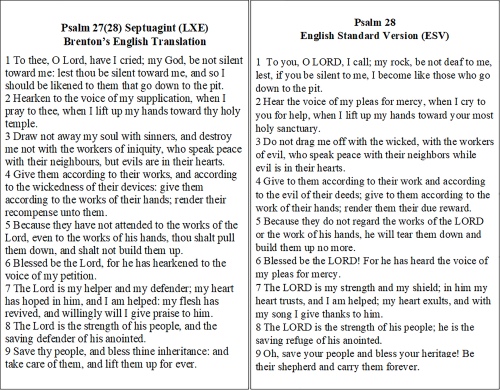

The text of Psalm 28(27 in LXX):

What I want to draw attention to in this post is the phrase found in verse 7: The Septuagint translation reads, “my flesh has revived,” while the ESV, based upon the Masoretic text, reads, “my heart exults.”

Consider this statement by Natalio Fernández Marcos, a current Septuagint scholar:

The Fathers of the Church did not formulate specific exegetical rules as did the rabbis, however they relied on a few principles or criteria of interpretation common to them all: the principle of the unity of the biblical text of the two Testaments, the interpretation of the Old in the light of the New, and the conviction that all the texts of the Old Testament spoke of Christ and of Christian mysteries. (Natalio Fernandez Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson (Brill: Leiden, the Netherlands, 2000), 342.

We can see by the principles of biblical exegesis the Church Fathers employed that their focus was upon Christ. After Jerome, however, the focus in the Western church, as distinct from the Eastern, shifted away from presenting Christ as central to Old Testament Scripture toward “correcting” the Church’s Old Testament text to place it in agreement with the Hebrew texts that rabbis were using and attested to. After Augustine’s time, the Old Greek text, and Latin texts based upon the Greek text, were substituted with a Hebrew text and translations that agreed with rabbinical texts. These rabbinical Hebrew texts had been edited centuries before the Masorites began copying them. Also, the Masorites introduced vowel points, which were not present in the original Hebrew texts. By the end of the first millennium, a single Old Testament Jewish Hebrew text, known as the Masoretic, dominated the Bibles produced by the Western Church. This remains so today, while the Eastern Church continues to use the Septuagint.

For all practical purposes, Western exegesis seemingly lost sight of the fact that the New Testament authors were largely quoting and relying upon the Septuagint as their Old Testament text. We find Western biblical theologians bending over backward, as it were, to explain the theology of the New Testament writers. The prevailing consensus was, “How did they ever get that out of this?” One common response to explain some of the surprising ways New Testament authors apply Old Testament Scripture was to say that the New Testament authors were “inspired,” i.e., they were specially permitted by the Holy Spirit to pull rabbits out of a hat–but we may not imitate them.

Some of the mind boggling mental gymnastics performed to explain the hermeneutics of New Testament authors involve words, phrases, and concepts such as sensus plenior, fuller meaning, allegory, typology, Midrash, Pesher, authorial intent, continuity or discontinuity of the Testaments, canonical approach, and others. Most of these terms and concepts are beyond the grasp of everyday Bible reading believers, including myself. I find that the simplest way to “find Christ in the Old Testament” is to read the Psalter from the Septuagint. (I make no claims of having read other portions of this translation.) When reading the Psalter from the Septuagint, all that’s needed is to let the text speak for itself.

For example, Psalm 28 provides a beautifully simple example of my meaning.

<<A Psalm of David.>> To thee, O Lord, have I cried; my God, be not silent toward me: lest thou be silent toward me, and so I should be likened to them that go down to the pit.

2 Hearken to the voice of my supplication, when I pray to thee, when I lift up my hands toward thy holy temple.

3 Draw not away my soul with sinners, and destroy me not with the workers of iniquity, who speak peace with their neighbours, but evils are in their hearts.

4 Give them according to their works, and according to the wickedness of their devices: give them according to the works of their hands; render their recompense unto them. (Psalm 27(28):1-4 LXE) (1)

For one whose ears are attuned to the crucifixion and the voice of David prophetically expressing the voice of Christ, the first three verses draw attention to the cross. Verse 1 indicates that the supplicant perceives God’s persistent silence towards him, and that his life is in grave danger (2). This accords well with Psalm 22:1, those words having been spoken by Christ on the cross and cited in the New Testament (Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34).

My God, my God, why have you abandoned me? I groan in prayer, but help seems far away. (Psalm 22:1 NET) (3)

Verse 2 is a direct statement of the psalmist’s action of prayer throughout the entire psalm–he is lifting his hands in supplication to his Father, just as Jesus did throughout his ordeal on the cross.

Then Jesus, calling out with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” And having said this he breathed his last.

(Luke 23:46 ESV)Psalm 31:5 Into thine hands I will commit my spirit: thou hast redeemed me, O Lord God of truth. (Psalm 31:5 LXE)

Verse 3 speaks of the cross in two manners. First, “Draw not away my soul with sinners,” can reference at least one of the two condemned men hanging on crosses of their own on either side of Jesus (4). Second, “destroy me not with the workers of iniquity, who speak peace with their neighbours, but evils are in their hearts,” is an apt description of Judas, who traveled with Jesus as one of his twelve and later betrayed him with the peaceful words, “Greetings, Rabbi!” (Matthew 26:49) and a kiss of brotherly fellowship. The prayers of verses 3b and 4 were answered when Judas was destroyed as a worker of iniquity (Matthew 27:3-10).

What do Verses 6-7 tell us?

6 Blessed be the Lord, for he has hearkened to the voice of my petition. 7 The Lord is my helper and my defender; my heart has hoped in him, and I am helped: my flesh has revived, and willingly will I give praise to him. (LXE)

Psalm 27(28) is a psalm whose action is straightforward: A supplicant cries out to the Lord, pleading with him not to ignore his prayers, lest he die and go to the pit. He asks that his soul not be carried away with evil doers, as though that were a possibility. He prays that the Lord will bring upon the evil ones his justice for their evil deeds, bringing back upon themselves what they themselves have done to others, vs 4. Verse 5 may be a choral or narrator’s comment that the Lord will indeed judge them with destruction that will not be undone (5). Verse 6 announces in first person again that the psalmist’s prayer has been answered, that God heard and replied. In verse 7, the psalmist rejoices in the Lord, reflecting upon the completed action of his prayer. He adds the fact that his body “has revived,” verifying the meaning of his words in verses 1 and 3 as pleas for escape from death. The words, “My flesh has revived,” signals resurrection. The final verses, vv 8-9, sound once more like the voice of the chorus or narrator, summing up the action of the psalm with the phrase, “The Lord is the strength of his people, and the saving defender of his anointed.” Additionally, verse 8 identifies the supplicant as the Lord’s “anointed,” his Christ in Greek, his Messiah in Hebrew (cf. Psalm 2:2 and others).

So why would the Septuagint translation of an ancient Hebrew text contain a revelation of resurrection, while our modern versions, based upon the less ancient Masoretic text, do not? Scholars are still using their best detective work to sort this out. However, they do know that the Septuagint translates a Hebrew text extant approximately 1,000 years before the oldest Hebrew texts the world now owns, the Aleppo (10th century) and Leningrad (11th century) Codices (6). Scholars tell us that while the Masoretic text can be reliably traced back nearly a millennia, the Septuagint received strong verification with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated between the first and third centuries BCE. Scholars thereby confirmed that back in those days, there existed more than one pedigree of Hebrew text (7). For whatever reasons, the Hebrew Masoretic text does not speak of resurrection in Psalm 28:7, while the Greek Septuagint version does. The Greek version and the Dead Sea Scrolls bear witness to the existence of an ancient Hebrew text that did include those words of resurrection.

Should a reader who applies Psalm 28(27 LXX) to Christ become alarmed that none of its verses are quoted in the New Testament?

Short answer: Not at all. You won’t be alone in seeing the resurrection in verse 7.

Encouragement Number One: The Existence of Good Texts and Translations

Under this point, first, consider the various translations available to us with this reading. We have already seen Brenton’s Septuagint. Next, the following is an original translation of Psalm 28:7 from the Masoretic Hebrew by Bishop Horsley of a prior century:

Jehovah is my strength and my shield; On Him my heart hath-placed-trust, and I am helped; My flesh hath-resumed-its-bloom [C], and from my heart I will praise Him. (Horsley, see footnote 8)

As explained in footnote 8, Horsley chose to substitute the Septuagint for the Hebrew and justified in his critical notes his reasons for doing so. “My flesh hath-resumed-its-bloom,” in Horsley’s translation is literal Greek.

The third translation is the Orthodox Study Bible, an original English translation from the Greek Septuagint used currently in many Orthodox churches. Verse 7c states, “And my flesh revived,” identical to Brenton. The study notes for this psalm begin, “Ps 27 is a prophecy concerning the death and Resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ…” (9)

Fourth, the recently completed New English Translation of the Septuagint, NETS, translates this portion of verse 7, “and my flesh revived.”

Finally, for those of you who have access to a Greek dictionary, the Greek text reads, “ἀνέθαλεν ἡ σάρξ μου” (Psalm 27:7 BGT).

Encouragement Number Two: Common Sense and Faith

In addition to the veracity of the Greek text, the New Testament itself encourages us to apply verses of the Psalter to Christ, even though we may not find all such verses quoted in the New Testament. Bear with me as I develop this argument.

First, even Jesus’s own disciples missed the message of the Old Testament with regard to the suffering, death, and resurrection of Christ. Jesus called them, “foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe” (Luke 24:25). We readers learn from this that the truths of Christ are apprehended by faith, but that these truths are manifest in Old Testament Scripture. After chastising his disciples for their lack of faith, Jesus walked back through these verses and taught his disciples (Luke 24:44-47). Now, Jesus blessed us with the gift of the Holy Spirit, who performs this same teaching function for us by walking us back through the Old Testament, including Psalms, and illuminating the text to our hearts, so that we, too, may discover and believe these things. Now we who have the advantage of hind sight, how is it that we should continue to miss these texts? Do we also wish that Jesus will say to us, “Foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe?”

As a second point in this argument, how many pages are contained in the Old Testament you use at home? And how many pages are in the New? My home Bible has 879 pages in its Old Testament and 262 pages in the New. The Psalms alone are 84 pages. The Psalms in my home Bible contain 32% of the number of pages in its New Testament. John the Apostle spoke to this subject. He said the following words:

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; 31 but these are written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:30-31 ESV)

Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written. (John 21:25 ESV)

Even though John made reference to Jesus’s “signs,” or miracles, and the things he did, the point holds that there is too much material to be written down. Moving on, the portions of the New Testament which are not the Gospels are all letters. Have you ever written a letter? And when have you ever written down everything in that letter that is on your heart to say? We don’t write that much. As another example, how many have ever written a report, a term paper, a discussion response, a letter to an editor of a newspaper, or the like? When we write such things, we give examples to support our viewpoint, but do we ever write down everything that we know?

The point is that the New Testament could not possibly quote all the Scripture in the Old that makes reference to Christ, simply for lack of space.

There is more to say on the topic of how Messianic references are established. Many scholars and the study portions of many editions of Scripture limit the Christological Old Testament prophecies to those which are exactly quoted in the New Testament. One of my study Bibles contains a chart on page 742 called, “Messianic Prophecies in the Psalms.” It lists 20 examples containing 22 verses. It gives Psalm 22 four separate listings, Psalm 69 two separate listings, Psalm 110 two listings, and Psalm 118 two. Did the author of this chart intend the reader to conclude that the portions of Psalms 22, 69, 110, and 118 that were not quoted are not therefore Messianic? Did they possibly mean that since other verses are not particularly quoted, we may not be certain that they are included and had better play it safe? This is called “atomization” of Scripture–deconstructing the Bible into tiny pieces answerable only to themselves. When I grew up, I thought that the New Testament quotations were like rabbits out of a hat. How did they get that out of this? I see now that I used to read my Bible as though it were separate little pieces disconnected one from another. When reading Psalms, I ignored the overall context–Christ–and the cohesive themes–Christ. I have since learned to read differently. Since Psalm 22 is given 4 separate listings, this means that all of Psalm 22 is about Christ, since it reads as a cohesive unit. The entirety of Psalm 69 is one cohesive unit, as well as Psalms 110 and 118. Since New Testament authors chose verses from these psalms to quote in connection with what later happened to Jesus, that most definitely does not mean that only those verses are about Christ. No writer quotes an entire book–all writers choose their quotations to make specific points, many of which are representative.

Compare this atomized approach to what Jesus most likely did. When Jesus taught his Emmaus Road disciples and later all the disciples gathered in the upper room, did he teach them to memorize that list of 20 examples, or did he teach them how to read the psalms with himself in view? I believe the latter.

Finally, one argument that evangelicals hear taught again and again is that the New Testament authors were “inspired.” Yes, of course they were. But all Christians who receive the Holy Spirit are also inspired. The New Testament authors alone were inspired to write the Bible. None of us has been chosen to write even one word of Scripture. However, we have been chosen to read the Bible. And the same Spirit that taught the New Testament authors how to write the Bible is the same Spirit, one and the same Spirit, that teaches us how to read the Bible.

How many reading this are teachers? Or, were you ever a student? Does a math teacher teach you how to do a certain set of particular math problems only, or does the teacher teach you how to “do math?” Does a history teacher teach only a specific set of facts, or does the teacher also teach students how to read history, perceive history in the making, think about history, and uncover historical facts beyond the material in the course? God gave his people the Bible, and he gave his people the Holy Spirit to help them read it. If the Spirit witnesses in your heart that Psalm 27(28) is about Christ and that verse 7 in the Septuagint English version is a prophecy of his physical resurrection, or a re-blooming, a re-viving, a re-vivifying, a bringing-to-life-again of his flesh, then please allow your faith in God to be stronger than what the academic pundits may be telling you about how you may and may not read Scripture.

__________

1 In some Bibles, the numbering of some psalms differs in the Septuagint. The Brenton edition that I own differs in its numbering system from my ESV. In Brenton’s LXE Psalm 27 is the ESV’s Psalm 28. The title of this blog follows the ESV numbering.

2 Most major English versions translate the Hebrew as, “the pit,” with the definite article; the Septuagint translator uses the definite article as well. NET writes, “the grave,” indicating of which pit, i.e., the pit of death, the psalmist speaks. Interestingly, however, the Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) and Pietersma’s translation found in the New English Translation Septuagint (NETS), both translate an optional grammatical indefinite, “a pit.” In other words, both the Greek and Hebrew allow for either a definite or indefinite interpretation. Context, then, is the determiner. What is the significance of this choice, definite or indefinite? “A pit,” I propose, keeps the reader’s mind focused on imagery local to the time of David, perhaps an actual pit in the ground, such as Joseph’s brothers threw him into, while “the pit,” definitely speaks of death, which does allow the reader’s mind to travel to Christ on the cross.

3 As a word to the reader to use more than one reference Bible, please hear that while NET has extensive notes about the Hebrew language and use of its words for this verse, including the fact that the literal, “the words of my groaning,” in Hebrew are sometimes applied to a lion’s roar and sometimes to human groaning, NET notes say nothing about the far more significant Christian citation of this verse in Matthew and Mark, which record Christ’s words while being crucified. I was forced to go to another translation, in this case ESV, to discover the exact NT citation of Psalm 22:1. A person reading Psalms for the very first time in their life might not realize that Christ spoke these words while dying, unless someone tells him or her.

4 I prefer the Septuagint here, because it distinctly speaks of the soul being drawn away, which can indicate the afterlife of punishment. Other English verses sound more as though it is the body that will be dragged off with sinners. If this is the case, however, then it would match the fact of Jesus’s life that indeed his body was not dragged off and disposed off with the two criminals. The rich man Joseph of Arimathea, a “highly regarded member of the Council,” (NET) buried Jesus alone in his own fresh tomb.

5 Bishop Horsley divides Psalm 28 with just such an “oracular voice,” in verse 5b. See Horsley, Samuel Lord Bishop. The Book of Psalms; Translated from the Hebrew: With Notes, Explanatory and Critical. London: 1815, Volume 1, 59.

6 Timothy Michael Law, When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, 21.

7 Ibid., 20-26. See also, “Psalm 28: Why the Septuagint? Part 1–Background,” by the author of this blog, available at https://onesmallvoice.net/2019/08/03/psalm-28-why-the-septuagint-part-1-background/, accessed 8/06/2019.

8 Praise God for his saints of former days! Bishop Horsley, see footnote 6, made an original translation from the Hebrew. For verse 7, in his critical notes, he writes that he consulted the LXX. He quotes the Greek text, and states that he confirmed this text with the Latin Vulgate. He believed the Septuagint translation, and posited a Hebrew text used by its translator in which two Hebrew words were transposed. He consulted the Syriac and found that it confirms his postulate for one of the Hebrew words. The good Bishop also writes, “Bishop Lowth approves this reading.” (Horsley, Psalms, Volume 1, 213-214).

9 Academic Community of St. Athanasius Academy of Orthodox Theology, Elk Grove, California. The Orthodox Study Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2008, 699.