What is the Septuagint? The Septuagint (LXX) is the ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament of the Bible, dated from the second to third centuries BCE. Why is the Septuagint important?

The LXX was the Bible of the authors of the New Testament. Its ubiquity can be seen not only in the quotations from the Old Testament in the New but also in the hermeneutic techniques and in many other forms of influence.

The LXX was transmitted in Christian circles once it was adopted as the official Bible of the Church.

…the LXX was also the Bible of early Christian writers and the Fathers of the Church, and even today continues to be the Bible of the Eastern Orthodox Church … The Greek version, either directly or through the Old Latin [which was translated from the Greek, not from Hebrew], provided the basis for Christian interpretation of the Old Testament, an interpretation which regulated the religious and social life of early Christianity (See footnote 1 for here and above).

Near the end of the first century and the completion of the writings that would comprise the New Testament, we enter into a period known as the Patristic age, characterized by the writings of the church fathers. …during this time the Septuagint was the Bible of the church: in its original Greek form, in its revisions, and in early translations into Latin used mostly in the North African church. The formation of Christianity–through preaching, teaching, apologetics, theological formation, and liturgical practices–depended almost entirely on the Septuagint as the Old Testament (2).

Many modern Bibles use the “Masoretic” Hebrew textual tradition for the Old Testament. In other words, the Hebrew text that is the basis of many modern translations was produced by the Masoretes. This textual tradition received its final, edited form in the centuries following the birth of Christ, although the oldest complete text is the Aleppo, dated at 930 CE. (3) On the other hand, many scholars agree that the Septuagint uses a Hebrew text that lies outside the Masoretic tradition. In other words, the Hebrew texts used as the basis for the Septuagint, which was translated in the centuries before Christ, possess a lineage distinct from the Hebrew texts which later became finalized as the Masoretic. Academic studies of the Septuagint textual tradition blossomed in the decades following the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

… the Hebrew Vorlage of the Greek Psalter may have differed in places from the extant Hebrew text (4).

The oldest layers of the Latin versions can attest text forms of great value for restoring the LXX and can even be used to recover some readings that have disappeared from Greek manuscripts and go back to a Hebrew text that is different from the Masoretic (5).

The above statements clearly contradict a popular notion that the current Masoretic Hebrew text is very nearly the original Hebrew Bible. As it turns out, there was more than one lineage of early Hebrew text. The world no longer has ancient copies of the Vorlage (prior version) of either the Septuagint translation or the Masoretic text. Textual critics must perform a great deal of detective work to piece together the facts of the origins of these Bibles (6).

Reconstructing the textual history of the LXX would be complicated enough if there had been but one Hebrew edition (preserved as the MT) from which the original Greek translation was made. The evidence of the Judean Desert material [i.e., Dead Sea Scrolls], however, confirms that the Hebrew text itself circulated in more than one form during the very time that the first Greek translation was being made. In other words, at least some of the elements of the LXX previously attributed to translation technique or recensional [editing] activity are now known to represent a Hebrew Vorlage different from the MT (7).

How does this affect you and I when we read the Bible?

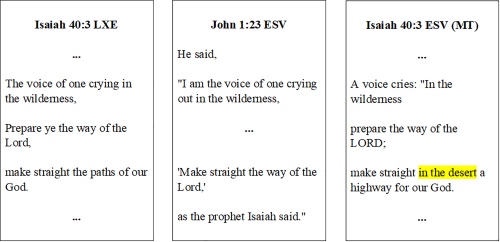

Have you ever wondered why Old Testament quotations by New Testament authors, such as the Apostle Paul and the gospel writers Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, often seem to differ from the same Old Testament passages in our modern Bibles? Based on the above discoveries, the answer lies in the fact that these authors likely used the Septuagint text, which differs somewhat in wording and focus from our modern English versions, which are mostly based upon the Hebrew Masoretic texts (8). For example, consider the following quotations:

When the reader of John 1:23 turns to the Old Testament to find the source of the quotation John uses, she will encounter a slightly different verse. In most modern versions, except those following the Greek Orthodox tradition, the Isaiah verse that John quotes has the additional phrase, “in the desert.” Well, John just left that out, you say. After all, he also left out the phrase, “Prepare the way of the Lord.” Okay, but this is not the only verse that differs. There are many such differences between our versions of the Old Testament and the New Testament quotations of it. Consider the following:

You took up the tent of Moloch and the star of your god Rephan, the images that you made to worship; and I will send you into exile beyond Babylon.’ (Acts 7:43 ESV)

But when you look up this quotation from Amos 5:26 in most translations, you will find that the quotation doesn’t match the OT verse:

You shall take up Sikkuth your king, and Kiyyun your star-god– your images that you made for yourselves, (Amos 5:26 ESV, the phrase “and I will send you into exile beyond Babylon” is from verse 27).

Compare the above modern translation based upon the Masoretic text with the Septuagint of Amos 5:26:

Yea, ye took up the tabernacle of Moloch, and the star of your god Raephan, the images of them which ye made for yourselves (Sir Lancelot Brenton translation of the Septuagint)

Clearly, the New Testament author was quoting the Septuagint (9).

Some of the differences in the Masoretic text tend to erase or minimize references to Messiah that come across strongly in the Septuagint. The following chart is from the “Orthodox Life” website: https://theorthodoxlife.wordpress.com/2012/03/12/masoretic-text-vs-original-hebrew/, accessed August 1, 2019.

In the chart above, the right hand column for Psalm 40:7 is very similar to the NIV, ESV, and KJV. The NET gives its own interpretive paraphrase, “You make that quite clear to me!” Note that the New Testament in Hebrews 10:4-10, far left column, appears to quote the Septuagint to its immediate right, rather than the Masoretic text underlying the quotation on the far right. If we were to follow the NET, then the messianic prophecy in Hebrews 10:5, “…a body you have prepared for me,” is transformed into, “You make that quite clear to me!”

As another example in the chart above, among the English versions NIV, ESV, KJV, and NET, for Isaiah 7:14, NET is the only translation that insists upon the phrase, “this young woman.” The other three translations do say, “virgin,” perhaps following the Septuagint’s lead.

Modern biblical versions sometimes consider the Septuagint to help decipher Hebrew that doesn’t always appear clear. An example of this is found in Psalm 22:16 (LXX 21:17), “They pierced my hands and my feet,” as in the Septuagint, versus, “like a lion, my hands and my feet,” as in many, but not all, extant Hebrew manuscripts. Although the NET Bible has a very long study note for the lion phrase, both its translation and its study note fall far short of the simple note found in the ESV for its translation, “They have pierced my hands and feet.” The ESV translators chose to follow extant texts that differ from the MT. They explain, “Some Hebrew manuscripts, Septuagint, Vulgate, Syriac; most Hebrew manuscripts like a lion they are at my hands and feet.” So, some Hebrew manuscripts do say, “They have pierced my hands and feet.” In explanation of the lack of specific NT citations in the far left column, the Gospel accounts of the crucifixion imply rather than state that the soldiers nailed Jesus’s hands and feet to a cross; they state he was “crucified,” which by definition means to be suspended by nails to a cross. In confirmation of this, Luke 24:40 reads, “And when he had said this, he showed them his hands and his feet.” John 19:37 reads, “They will look on him whom they have pierced.” Again, John 20:25 speaks of nail marks in Jesus’s hands. But once again, the main point is that the Complete Jewish Bible and the NET choose to pass by a prophecy of the crucifixion in Psalm 22:16 when they choose to follow certain Hebrew texts rather than the Bible of the early Christian church, the Septuagint. And please note again that some Hebrew texts do contain what later became the Christian reading of this text.

The Septuagint Today

- Carefully consulting the study notes of the ESV reveals that this recent translation often follows the reading of the Septuagint, Vulgate, and Dead Sea Scrolls in verses that differ significantly from the Masoretic text. Some of the notes indicate the comparative readings, as in Deuteronomy 32:43. Interestingly, the NET, which translates only the Masoretic Text for the Deuteronomy verse, gives no study notes at all, even though this is a verse with several instances of multiple readings.

- The Orthodox faith has always used the Septuagint as their Old Testament Bible. According to Wikipedia, the world wide population of Eastern (Greek) Orthodoxy is 200-260 million people.

How does this impact us? Think about this. What is your favorite biblical translation, the one you use in your personal devotions and worship on a daily basis? Would you call that book, “the Bible?” Isn’t it for all practical purposes your Bible? Truth is that whenever a people group receives a Bible in their own tongue and uses it regularly, it becomes for them the Bible. If I happen to live in Papua New Guinea and I am a native, and if I receive a Bible that has been translated into my native language, then that translation for me is the Holy Word of God. Chances are it is the only Bible I will ever read.

Perhaps the most important cultural impact of the LXX in early Christian literature is due to the many translations of it into the main languages of late antiquity.

Not only did Christianity adopt a translated Bible as the official Bible, but from its beginnings it was a religion that favoured translation of the Bible into vernacular languages. Unlike Jewish communities, the Christian communities did not feel themselves to be chained to the Hebrew text as such but only to its contents, nor were they tied to the Greek text of the LXX. The new translations, as distinct from [what (inserted to correct text)] happened with the Aramaic Targumim, became independent and took the place of the original in the life of the communities. This attitude conferred on the new versions of a Bible a status unlike that of the Jewish translations. They were not merely an aid to understanding the text but they replaced the original with authority. Hence, biblical translation is spoken of as a specifically Christian activity.

It is appropriate to note that, with the exception of the Aramaic translations, most of the ancient versions of the Bible were made from the LXX and not from the Hebrew. Not even the Peshitta or the Vulgate, most of which was translated from Hebrew, are immune to the influence of the LXX.

–The entire quotation above is contiguous from Natalio Fernandez Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson (Brill: Leiden, the Netherlands, 2000), 346.

Worldwide, among believers of all times and places, there is not now nor has there ever been one, single, original Bible. And, like the Ark, Aron’s staff, and the cross of Christ, if there once were such a Bible, it is quite unavailable to everyone now. Believers have always used the Bible they like and the one that is at hand. And why should any believer be told by a group of remote scholars that “their” Bible is incorrect for purposes of “exegesis?” Modern scholarship has declared that Jesus’s followers and the authors of the New Testament used the Septuagint as their Bible. For these people, the Septuagint was God’s Holy Word.

But even deeper than all written texts and translations, God himself protects the substance of his Word by the gift of the Holy Spirit, who indwells each believer’s heart. The aggregate of the Spirit inspired beliefs of all Christians creates what is known as the “rule of faith.” It was by the “rule of faith” that the early church established the traditions of what was genuinely from the Lord and what was not. The “rule of faith,” not a body of influential and elite scholars, determined which gospels and which letters were genuinely from God. After many centuries, an important standard for canonicity was the “rule of faith,” that is, what the church as a body determined was orthodox, based upon what was spoken by the apostles and later repeated by word of mouth to all believers. What the “rule of faith” determined was Scripture, became New Testament Scripture (10). A group of church elders did no more than put their seal of approval upon those letters and gospels which the body of Christian believers through usage over time agreed to be the apostles’ teaching. This explains why there are two Bibles for two branches of Christian faith, namely, the Western and the Eastern.

Galatians 5:1 For freedom Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not be subject again to the yoke of slavery. (NET)

Are we free to choose? Scholars come, and scholars go, but the Word of our God stands forever. Personally, in my private devotions and worship, almost since my beginning in Christ, I have relied upon the Septuagint Bible and its English translation by Brenton for the book of Psalms and the book of Isaiah. I love this version because I find it speaks of Christ more directly than many of our other English choices. And isn’t Christ who the Bible is entirely about?

__________

1 Natalio Fernandez Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson (Brill: Leiden, the Netherlands, 2000), 338-339.

2 Timothy Michael Law, When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible (Oxford University Press: New York, 2013), 118-119.

3 “The Aleppo Codex, the oldest Hebrew Bible that has survived to modern times, was created by scribes called Masoretes in Tiberias, Israel around 930 C.E. As such, the Aleppo Codex is considered to be the most authoritative copy of the Hebrew Bible. The Aleppo Codex is not complete, however, as almost 200 pages went missing between 1947 and 1957.” Overview summary by Bing, original article available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleppo_Codex, accessed August 3, 2019.

4 Karen H. Jobes and Moises Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint (Baker Academic: Grand Rapids, 2000), 278.

5 Natalio Fernandez Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible, translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson (Brill: Leiden, the Netherlands, 2000), 357.

6 Jennifer M. Dines, The Septuagint (T&T Clark Ltd: New York, 2004), 24 and 41-62.

7 Karen H. Jobes and Moises Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint (Baker Academic: Grand Rapids, 2000), 281. See pages 273-287 for further information on the history of the text of the Septuagint.

8 An interesting, easy-to-read article on this topic appears at this link: https://www.biblestudytools.com/bible-study/topical-studies/does-the-new-testament-misquote-the-old-testament.html. Another appears here: http://orthochristian.com/81224.html.

9 See Fr. John Whiteford, “The Septuagint vs. the Masoretic Text“ in Orthodox Christianity, http://orthochristian.com/81224.html, accessed August 1, 2019.

10 Andreas J. Kostenberger, L. Scott Kellum, Charles L Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown (B&H Academic: Nashville), 2009, 9. See also https://www.earlychurchtexts.com/public/tertullian_on_rule_of_faith.htm, accessed 08/02/2019.